When I lived in Naples Florida for two years (80-82), I met and became friends with many in the Cuban community of South Florida. I found Cubans generally to be very devoted to family and possessing a strong work ethic. Here’s a few important anecdotes that I recall:

I interviewed one American (married to a Cuban) who was actually part of the Bay of Pigs invasion, sponsored and supplied by our government, but after endorsing the initial landing, President Kennedy abandoned any support and the invasion failed miserably. The Cubans never forgave that betrayal and are to this day largely Republican politically, detesting the Democrats. My friend was one of the captured and spent time in a Cuban jail. His story was not a happy one.

One family that were members of my church were farmers who lived on the Isle of Pines. When Castro took power, their two boys were taken from them and sent to the state school for which education, which consisted of some classes and half a day’s work in the fields. One was drafted into the Cuban Army and sent to Angola. He was never heard from again. I wrote a poem titled, “They Took the Baby Away,” published in a political magazine entitled, Voice of Freedom. You can read the poem and more about this family HERE:

Once, I needed to pick up someone at the Miami airport. The night before, I attended a Church of Christ congregation in Miami and spent the night in the church building. I was so impressed with the members’ warmth and love and they gladly shared stories about their lives in Cuba. I may add stories to this post from time to time. I’m searching for some photos to go along with the stories.

These are just a few of the stories I could share, but if you would like to read more, I would recommend the following books:

These are just a few of the stories I could share, but if you would like to read more, I would recommend the following books:

- Freedom Flights: Heirs of the Cuban Revolution Tell Why They Grew Disenchanged with Castro, and How they Were Obliged. to Flee His Regime.

- Los Gusanos: A novel by John Sayles.

- Bay of Pigs: by Peter Wyden

I lived in South Florida (Naples) for a couple of years and there I encountered and learned much about Cuba and the thousands who had managed to flee Cuba. Last night, I watched a Netflix movie, WASP NETWORK, and this brilliant film revived many memories and feelings I had experienced as I worked among and with the Cuban community. The 2019 film is based on a book, The Lost Soldiers of the Cold War: The Story of the Cuban Five, (a book I just ordered). Oliver Assayas wrote and directed the movie. Much of the dialogue is in subtitled Spanish. The actors’ performance (including Penelope Cruz) is amazing. The plot is based on the lives and experiences of Cuban spies operating in South Florida in the 1990s. There are no happy endings for the Cuban Five.

I lived in South Florida (Naples) for a couple of years and there I encountered and learned much about Cuba and the thousands who had managed to flee Cuba. Last night, I watched a Netflix movie, WASP NETWORK, and this brilliant film revived many memories and feelings I had experienced as I worked among and with the Cuban community. The 2019 film is based on a book, The Lost Soldiers of the Cold War: The Story of the Cuban Five, (a book I just ordered). Oliver Assayas wrote and directed the movie. Much of the dialogue is in subtitled Spanish. The actors’ performance (including Penelope Cruz) is amazing. The plot is based on the lives and experiences of Cuban spies operating in South Florida in the 1990s. There are no happy endings for the Cuban Five.

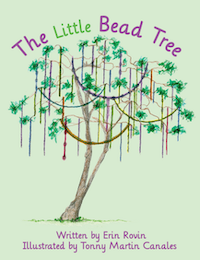

The Little Bead Tree by Erin Rovin, is a sweet story for children and for anyone of any age who loves trees and Mardi-Gras. As many know, during and for days after the festival, one can see a long line of grand oak trees along Saint Charles Avenue covered with strings of beads tossed upon their branches for good luck. This children’s picture book illustrated with soft beautiful art is the story of how a grand old oak tutors and encourages a young tree, explaining the need of the youngster to have patience and belief that, though small in size, it is a special tree who will one day see and experience great and happy things if it will stay grounded and trust.

The Little Bead Tree by Erin Rovin, is a sweet story for children and for anyone of any age who loves trees and Mardi-Gras. As many know, during and for days after the festival, one can see a long line of grand oak trees along Saint Charles Avenue covered with strings of beads tossed upon their branches for good luck. This children’s picture book illustrated with soft beautiful art is the story of how a grand old oak tutors and encourages a young tree, explaining the need of the youngster to have patience and belief that, though small in size, it is a special tree who will one day see and experience great and happy things if it will stay grounded and trust. About the author: Erin Rovin lives in the New Orleans area. Her previous work and writings include investigative reporting, print and online articles, and a stint as a New Orleans City Guide writer. Previous books include the Adventures of Little Laveau series of children’s books. She has a BFA from the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. She has worked in the film industry with shows, including Dancing With the Stars.

About the author: Erin Rovin lives in the New Orleans area. Her previous work and writings include investigative reporting, print and online articles, and a stint as a New Orleans City Guide writer. Previous books include the Adventures of Little Laveau series of children’s books. She has a BFA from the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. She has worked in the film industry with shows, including Dancing With the Stars.