Thirty Days to Halloween, Day 28: The Ice Caves and the Chindi

When the unclean spirit is gone out of a man, he walketh through dry places, seeking rest; and findeth none.–Matthew 12:43

EDUARDO STEPPED UP ON A BOULDER AND SCANNED THE DESERT FOR THE NEXT CAIRN MARKING THE TRAIL. The heat waves shimmered into the sky from the desert ground and the distant mountains moved and bent in the refracted air. After he spotted the cairn, he lifted his straw cowboy hat and wiped his forehead with the long sleeve of his khaki shirt. He slicked back his shoulder-length black hair with his hand, then slid down the boulder. Sheridan and Bronwynn, his two fellow hikers, were studying a topographic map spread on the ground.

EDUARDO STEPPED UP ON A BOULDER AND SCANNED THE DESERT FOR THE NEXT CAIRN MARKING THE TRAIL. The heat waves shimmered into the sky from the desert ground and the distant mountains moved and bent in the refracted air. After he spotted the cairn, he lifted his straw cowboy hat and wiped his forehead with the long sleeve of his khaki shirt. He slicked back his shoulder-length black hair with his hand, then slid down the boulder. Sheridan and Bronwynn, his two fellow hikers, were studying a topographic map spread on the ground.

“I spotted the next cairn, Sheridan,” Eduardo said. “Shinny up this rock and take a look. The ice cave is an hour beyond the cairn.”

Sheridan spat dry phlegm from his mouth and took a long drink from his water bottle. He stepped up on the boulder and scanned the dark ground surrounding them. “You’ve got better eyes than I do, Eduardo. I can’t tell which pile of rocks you’re talking about.”

Eduardo squinted his eyes, focussing on blurred movement in the brush. A roadrunner battled with a rattlesnake. Both creatures seemed abnormally dark, their midnight-dark coloration a camouflage in the rugged volcanic terrain. A strange contrast to what desert visitors would see fourteen miles south, where the black New Mexico landscape would give way to white gypsum sands, and there the skins of the same animals would be abnormally light.

Edward saw Bronwynn shudder when a scorpion scurried past the toe of her boot.

“God, even the scorpions are black here,” she said. “It’s so damned hot out here. Are you sure there’s ice caves out here?”

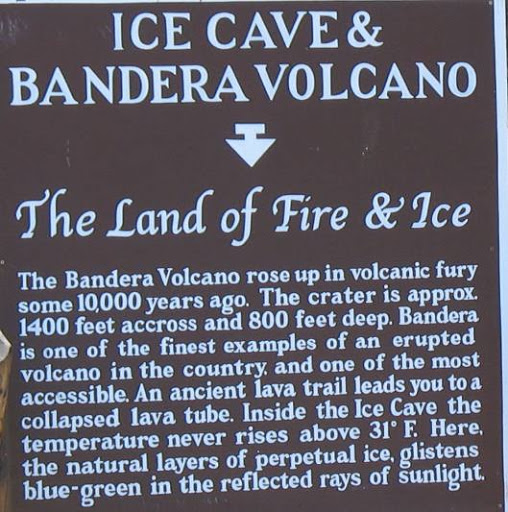

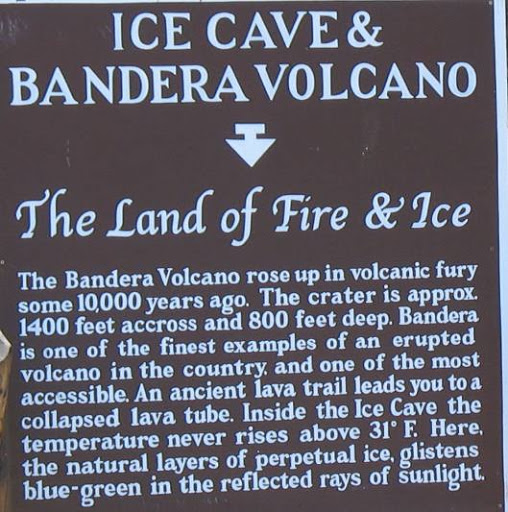

“Yeah,” Eduardo said. “I’ve seen them. And the temperature in them never gets above 31 degrees. Hard to believe, isn’t it? Ice caves in the Valley of the Fires.” He handed Bronwynn his water bottle.

Bronwynn chugged down several swallows and handed the bottle back to him. “I don’t think I like desert camping. Everything either bites or stabs you. My socks are full of cactus spines. And the landscape looks like Mars or something. Look at my boots. The rocks have cut them up so bad I’ll have to walk back barefoot.”

Eduardo looked down at his own boots. They were gouged and cut from their walk as if a madman with a razor had slashed out at his feet. “Yeah, it’s a rough hike, but seeing this cave will be worth the scratches and blistered skin. Think about it. How many people have ever seen an ice cave in the middle of a desert? And I’ll get some great photos and a good magazine article out of it.”

“What will we get?” Bronwynn asked.

“An unforgettable adventure and my gratitude for your company,” Sheridan said.

“The trip’s already unforgettable,” Bronwynn said. “I’ll never come to the desert again.”

They passed through a thicket of scrub juniper and cactus skeletons and came upon a jacal. An old woman, her skin wizened and blackened from the sun, sat in the shade of the brush hut picking at her tangled gray hair with bony hands.

Sheridan waved. “Hello. We’re students from the University of Texas in Austin. Do you mind if we talk to you?” The old woman stared at them but said nothing. Sheridan glanced at the others. “What do you make of this, Eduardo?”

“Bruja,” he said. “She’s a witch. They’re the only Indians that live alone in the desert. Let’s go on.”

“Ah, come on,” Sheridan said. “Let’s go meet her. This might be a real photo opportunity. I’d like to meet a real witch.”

“No, you wouldn’t,” Eduardo said.

“Maybe she’s got something cool to drink,” Sheridan said.

“That’s real funny, Sheridan. There’s hardly any water out here. That’s why we’re toting two gallons of water each for a two-day hike. I wouldn’t eat or drink anything she offered anyway.”

“Why not?” Sheridan said.

“Witches poison people if you’ve got something they want.”

“What would we have that she’d want? It’s hard for me to understand how you can spend all your money getting a journalism degree, yet still be eaten up with Indian superstition.”

“Shut the hell up, Sheridan. Alright, we’ll go up to her and you take your picture, but we can’t stay long if we want to reach the cave before dark.”

Eduardo walked up to the woman. He bowed his head slightly and greeted her in Navajo.

She shook her head. “Soy Apache. Sientate,” she said.

“What did she say?” Bronwynn asked.

“She’s Apache,” Eduardo said. “But I think she knows enough Spanish to talk to us. She said we could sit down.”

They pulled off their packs, sat down in the shade near the woman, and gulped down some water from their bottles. Sheridan took his camera from his pack and pointed it at the woman.

The woman straightened herself and smiled, revealing a few jagged and yellow teeth. After Sheridan took the picture, she slumped back against the hut wall. “Donde van?” the woman said. She held out a rusty tin cup that Eduardo filled with water from his bottle.

“To the ice caves,” Eduardo said. The woman shook her head, so he repeated himself in Spanish. “A las cavernas del hielo.”

The old woman nodded. “Frio, muy frio. Lago de invierno. Lago de muertos.”

The woman held out a basket filled with fruit-like pods. “Quiere las tunas?”

Sheridan picked out one. “Gracias,” he said. “Looks like prickly pear apples.”

“You idiot,” Eduardo whispered. “It may or may not be prickly pear. A witch can poison or drug you.”

Sheridan took a bite. “It tastes like prickly pear. Don’t be so paranoid.” Sheridan reached into his pack and pulled out a Granola bar and handed it to the woman.

She unwrapped the bar, threw the paper to the ground, and stuffed the bar into her mouth. After wiping her mouth with her arm, she pointed to Bronwynn’s ponytail. “Damelo,” she said. “Damelo.” She reached over and fingered the elastic band holding back Bronwynn’s hair.

“She wants you to give her the band,” Eduardo said.

Bronwynn smiled, slipped off the band and handed it to the woman, then reached into the pocket of her hiking shorts and for another band to use on her own hair. The woman grinned and pulled back the tangled mass on her head and slipped on the band. “¿Está bien?” she said, turning her head from side to side.

“Está bien,” Eduardo said. “Okay, Sheridan, you’ve met your witch. We better hit the trail.” He stood up.

The woman held up a small serpent-shaped stick, pointed it at a javelina skull hanging on her hut, then pointed in the direction they were going. “No va allá,” she said. “Chindi, mal, mal.”

“She says we shouldn’t go to the cave,” Eduardo said. “Says something about the chindi being there.”

“Sí, sí, chindi, chindi,” the woman said. She raised her hands like they were claws and growled.

“What are chindi?” Bronwynn asked.

“Ghosts,” Eduardo said. “The earth-surface dead. I’m not sure what the Apache think, but Navajos believe that when someone dies, the evil part of their spirit often returns to torment travelers and settle grudges with people they knew.”

“Do you believe that crap, Eduardo?” Sheridan said.

“I’m half Navajo, so I guess I half believe it. Grandmother said the chindi killed Grandfather. One night they chased their flock of churro sheep into the desert and attacked and mutilated several of them. Grandfather went out to herd the flock back, and a chindi jumped out and clawed him. Gave him the ghost sickness.”

“Oh, that’s great, Sheridan” Bronwynn said. “You’ve brought us to a haunted desert. What happened to your grandfather when he got this ghost sickness?”

“First, he got really sick. The family knew he was dying, so they carried him out of the hogan and laid him under his favorite shade tree. Two nights later he died. Then we brought him here to the desert and buried him near the ice cave we’re going to.”

“They let him die outside alone?” Bronwynn said.

“What else could they do?” Eduardo said. “He had the ghost sickness. If he had died inside, she would have had to burn the hogan to keep the evil spirit from coming back.”

“But to die alone!” Bronwynn said.

“We all die alone, Bronwynn,” Eduardo said. “Every culture has its demons. Navajos have the chindi. I guess if one demon doesn’t get you, another one will.”

“Sí, sí, chinde, chinde,” the old woman said. “Ustedes van a jornado de muertos.”

“What did she say, Eduardo?” Bronwynn said.

“She said we’re going to a dying place.”

* * *

AFTER they passed the next cairn, they came upon a string of kipukas. Past volcanic activity had chemically altered the large sandstone islands’ color so that they had yellow and pink surfaces, and in other spots, the sandstone had metamorphosed into giant blocks of quarts. Beyond, black volcanic rock and obsidian covered the ground. Many of the stones were green-streaked with a patina of red and purple, and the colors danced like flames in the sunlight.

They crossed a barbed wire fence, with a NO TRESPASSING sign wired to one of the old mesquite posts. “We’re trespassing,” Bronwynn said as they slipped through the wire.

“What the owners don’t know won’t hurt them,” Sheridan said. “Besides, the NPA has prohibited access to all known ice caves and won’t even reveal their locations. It’s actually good this cave is on private property. The government might not even know it exists.”

When Sheridan heard a snort and a sharp barking sound, he looked to his left and saw several javelinas bedded down in the shade of some junipers. He stomped his foot and the javelinas jumped, crashed into the brush, and vanished.

Bronwynn jumped forward and grabbed Sheridan’s arm. “What was that?” she said.

“Javelina,” Eduardo said. “They’re all over this part of the country. Watch out for them. They’ll tear your ass up with those long teeth.”

“They didn’t seem dangerous to me,” Sheridan said. “I thought I scared them off rather easily.”

“This time,” Eduardo said.

Bronwynn pointed to a deer carcass under one of the junipers. “Yuk!” she said. “They were eating something dead.”

“They’ll eat anything,” Eduardo said. “Live or dead.”

At sundown, they came to a rise of ground with a tumbled mass of boulders and volcanic rock, and Eduardo set down his pack. “Okay, we’re here. The cave’s right up there in those rocks, by the two biggest boulders.”

A thick black stream swirled from the rocks and then separated into specks that vanished into the sky.

“Look at all those birds,” Bronwynn said.

“Those are bats,” Eduardo said. “They live in the caves.”

“Sheridan, you didn’t say anything about bats being in this cave,” Bronwynn said.

“Don’t worry, they don’t bite. I just hope we don’t have to wade through a lot of guano. Let’s go take a look at the cave,” Sheridan said.

“Wait till tomorrow,” Eduardo said. “The ground’s rough and it would be easy to break a leg in the dark. There’s a bunch of lava tubes up there and since I haven’t been here in a long time, I’ll need daylight to find the right hole to crawl into.”

After a supper of crackers and sardines, Sheridan pulled a bottle from his pack. “Hey, I brought some mescal,” Sheridan said. “Let’s celebrate reaching the cave. You want some, Eduardo?”

“Sure. But I can’t believe you’d bring that rot-gut stuff when you could have bought some perfectly good whiskey.”

“Just felt mescal would fit the setting.” Sheridan poured some into each of their cups. “Here try a sip, Bronwynn.”

Bronwynn took a small swig and shuddered and handed the cup back to him. “God, it tastes like kerosene. How can you drink that?”

As darkness fell, stars blanketed the sky and the moon rose. Sheridan lit a lantern, and they listened to the wind as it wound its way through the brush and rock formations.

“Listen,” Bronwynn said. “Sometimes the wind sounds like someone’s laughing or talking. It’s weird.”

“Desert’s a strange place. Maybe it’s the chinde,” Eduardo says. He stood, stretched his arms, and smiled. “Or it could be skinwalkers. Maybe they don’t like us camping here.”

“You mean they might think we’re trespassing?” Bronwynn said. Her white face glowed in the light of the lantern and the moon.

“Would you like someone camping on your front lawn?” Eduardo replied. “I read about people disappearing out in the desert. Some places possess evil powers. Witches will gather in secluded places like this take over the corpses of travelers who die to harm people who anger them. They can shapeshift into animal form.”

Bronwynn shuddered. “Shut up, Eduardo. You’re creeping me out.”

“No more ghost talk,” Sheridan said. “Let’s get some sleep.”

When Sheridan stood up, he staggered and nearly fell. “Whew! That mescal’s pretty stout.” After he recovered his balance, he and Bronwynn spread out their sleeping bags on a bare slab of sandstone. They took off their boots and lay down. Sheridan could feel the hardness and coarseness of the stone against his back even while he felt the softness of Bronwynn’s arms around him. Some coyotes howled neared them. Sheridan sat up and saw two coyotes sitting on their haunches on the large boulders Eduardo said marked the entrance to the cave. Sheridan lay down again and when he closed his eyes, he felt like he was tumbling, and when he opened them, the stars spun wildly. “God, I hope I don’t get sick,” he whispered to Bronwynn. “I think this stuff is fermenting in my stomach.”

“You’ll be alright,” Bronwynn said. “Just don’t drink anymore. You always try to do too much of everything. Just quit talking and go to sleep.”

* * *

EDUARDO could hear Sheridan snore. He poured himself another full cup of the mescal. He drained it, then turned off the lantern and lay down on his own sleeping bag. As he drifted into sleep, he heard a snort and felt hot breath on his face. He jerked up and saw javelina by his bedroll. Its eyes glowed red in the moonlight and the coarse hair on its back bristled. The javelina snorted again and its nostrils flared as it popped its long front teeth. Eduardo kicked out at the javelina, grabbed a rock and hurled it. The rock struck the pig on its thick collar and ricocheted to the ground.

“Shoo, you sorry excuse for a pig. Git out of here!” Eduardo shouted.

The pig turned and ran into the brush a few feet, then stopped and turned around again.

When Eduardo jumped up and ran at the pig, it disappeared into the brush. Eduardo picked up two more rocks and followed. He threw the rocks hard at a dark spot of ground where he thought the pig might be. He heard movement and strained his eyes to find the shape of the javelina in the shadows. Instead, he saw a human shape rise and walk toward him.

“Who’s there? Bruja, is it you? Even a kook like you should know better than to come into a camp at night!”

The shape stepped back into the shadows.

“Why don’t you show yourself?” he shouted.

Bronwynn shook Sheridan.

“What is it, Bronwynn?”

“Listen. What’s wrong with Eduardo?”

Sheridan sat up and willed his mescal-beaten eyes to focus on Eduardo who was standing and shouting at the darkness.

“God he must be really drunk,” Bronwynn said. “Listen to him. Who’s he talking to? Maybe the desert really does make people crazy.”

“He’s probably just had too much mescal. Hey! Eduardo, you okay?”

Eduardo wobbled on his feet and pointed at the desert. “A javelina came into camp and after I ran him out, I saw someone in the brush. I can’t find my flashlight, or I’d go out and kick their ass.”

“You’re drunk, Eduardo, and you’re seeing things,” Sheridan said. “No one’s out here.”

Eduardo sat down on his sleeping bag, still looking out into the dark. “I tell you someone’s outside our camp. I can hear him moving in the brush now. Right behind me. Put your light on them. For a moment, I swear I thought it was my grandfather.”

Sheridan stood, turned on his flashlight, and scanned the ground behind Eduardo. The beam caught several pairs of red eyes close to the ground. “It’s feral pigs, Eduardo. That’s all it was.”

“It could be skinwalkers or a chindi.” Eduardo picked up another rock and threw it. The herd of javelinas squealed and snorted and ran wildly away from the camp. Sheridan followed them with the beam of the MAG-LITE. The herd stopped for a moment as another one joined them and then they vanished into the desert night.

* * *

SHERIDAN woke in the gray twilight of dawn, shook out his boots to make sure they contained no scorpions or snakes, and made coffee. Eduardo lay sprawled on the bare ground, the empty bottle of mescal in his hand. Sheridan sipped his coffee and watched the sunrise, and when the soft reds of the dawn sky disappeared into an explosion of light, he woke Bronwynn and Eduardo.

“Up and at’em, campers. Let’s get on to this cave.” He took each a cup of coffee.

Eduardo sat up. “I don’t know if I can get up.”

“Maybe it’s true what they say about Indians and firewater.”

“Screw you, Sheridan. Got any aspirin?”

They ate a breakfast of oatmeal and orange drink and enjoyed the cool of the desert morning. Then Eduardo led them to a pair of basalt boulders near the mouth of the cave.

Sheridan glanced at the towering rock surface and smiled. “Look, petriglyphs.” Carefully etched onto the smooth surface of the stones were geometric symbols, a seven-foot horned rattlesnake, a javelina, and several masked people. “You didn’t tell me about this, Eduardo.”

“I’d forgotten about them.”

“How could you forget something like this?” Sheridan said.

Bronwynn put her finger on one of the human figures and snickered. “Look, he’s anatomically correct. So what tribe of Indians lived out here?”

“The Jornodo Morgollón,” Sheridan said. “Most of them were eaten by the volcano that made this valley and the ice caves. I don’t know if they were the ones that made these though.”

“What does Jornodo Morgollón mean?” Bronwynn asked.

“The stupid ones,” Eduardo said. “No one in their right mind would live out here. My father and grandfather came to the ice cave once or twice a year. I always hated it when they brought me with them. But they said there was big medicine here and that I needed to make peace with the desert.”

Sheridan smiled. “Did you?”

“No.”

Sheridan laughed and after he finished taking pictures of the petroglyphs, Eduardo pointed to a small hole in the ground near the boulders.

“There’s your ice cave entrance,” Eduardo said.

“That little hole is a cave?” Bronwynn said.

“It’s a lava tube, and it’s deep. It gets a little wider once you’re inside.”

“How far down is the ice?” Bronwynn said.

“Seems like we crawled an hour or so before we reached the ice.”

“Let’s go in,” Sheridan said. “I want to be first.” Sheridan stuck his head inside, turned on his mag light and peered down the shaft. After he put on his leather gloves, he slid down the lava vent feet first. He felt the jagged and rough surface of the lava against his legs. A few yards down the tube widened. “So far, so good,” Sheridan said. “The slant is not too bad. You two might as well come on. Be careful. The rocks are sharp.”

Eduardo and Bronwynn joined him, and they crept slowly down the lava tube. The cramped size of the tunnel slowed down their progress. As they went deeper, the temperature gradually decreased, and in spite of the exertion of moving, Sheridan felt chilled. The cave widened into a large room and there they found the ice. A thick layer covered the walls, floor, and ceiling of the cave. Sheridan had heard that the ice in some caves was up to twenty feet thick. The ice had a blue-green tint and the color reminded Sheridan of the color of the ocean. “Look at how blue the ice is, Bronwynn, blue as your eyes, bluer than the sky.”

“I thought it would look more like Carlsbad Caverns and have ice cycles,” Bronwynn said. “I’m cold now. How long do we have to stay in this icebox?”

“You two can go back to the camp if you want, but I’ve got a lot of work to do here. This is fantastic,” he said. “Do you know how old this ice is?” He pulled his camera, tape measure, and note pad out of his daypack.

“I’m ready to go too,” Eduardo said.

“So go. I’ll be up later.”

“Better hurry, it will be dark soon,” Eduardo said.

* * *

SHERIDAN finished his last roll of film, made some final notes, put a small sample of the ice into a jar, and began the long crawl back to the surface. He rolled out of the opening and walked into their camp. Bronwynn and Eduardo looked to be fast asleep in their sleeping bags. Exhausted from his journey into the ice cave, he drained the bottle of Mescal and fell into a troubled sleep. He didn’t hear Bronwynn and Eduardo call out to him.

* * *

AT sundown the next day, the Apache woman stood over the bodies of the campers. Sheridan had been staked out spread-eagle to the ground. Ants covered much of his body and thorns and cactus spines had been pressed deep into his white flesh, but he was not dead yet. The mutilated bodies of Bronwynn and Eduardo lay on either side of him. She stripped the bodies of their clothes and emptied their backpacks on the ground and filled one of the packs with everything she wanted. She looked toward the cave and saw the two coyotes sitting on their haunches by the entrance, and the bats rising from the dark holes of the earth into the sky. The wind stirred and she heard the malignant whispers of the chindi and knew they were near. For protection, she fingered the amulet pouch around her neck, a pouch containing the gall bladders of a bear, coyote, and deer. Sheridan moaned loudly, and she could hear the herd of javelinas crashing through the brush toward him. “Sí, sí, chindi, chindi. Voy,” she said. She rose, and dragging the heavy pack, hurried back toward her jacal while the javelinas fed on the three travelers.

EDUARDO STEPPED UP ON A BOULDER AND SCANNED THE DESERT FOR THE NEXT CAIRN MARKING THE TRAIL. The heat waves shimmered into the sky from the desert ground and the distant mountains moved and bent in the refracted air. After he spotted the cairn, he lifted his straw cowboy hat and wiped his forehead with the long sleeve of his khaki shirt. He slicked back his shoulder-length black hair with his hand, then slid down the boulder. Sheridan and Bronwynn, his two fellow hikers, were studying a topographic map spread on the ground.

EDUARDO STEPPED UP ON A BOULDER AND SCANNED THE DESERT FOR THE NEXT CAIRN MARKING THE TRAIL. The heat waves shimmered into the sky from the desert ground and the distant mountains moved and bent in the refracted air. After he spotted the cairn, he lifted his straw cowboy hat and wiped his forehead with the long sleeve of his khaki shirt. He slicked back his shoulder-length black hair with his hand, then slid down the boulder. Sheridan and Bronwynn, his two fellow hikers, were studying a topographic map spread on the ground.