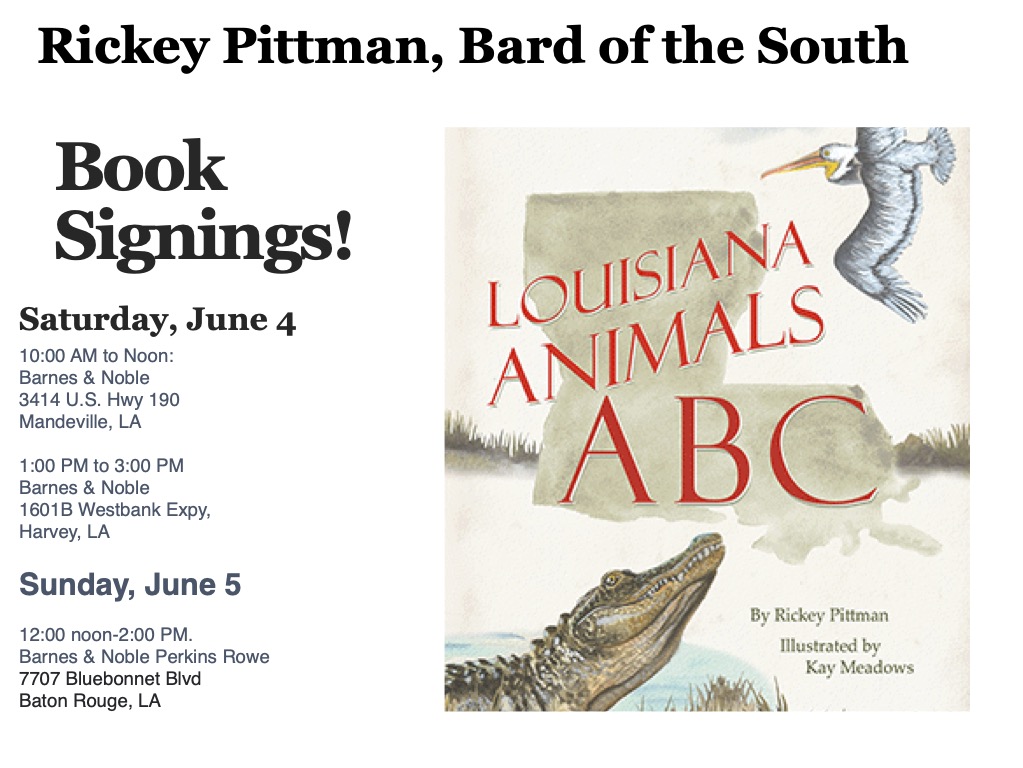

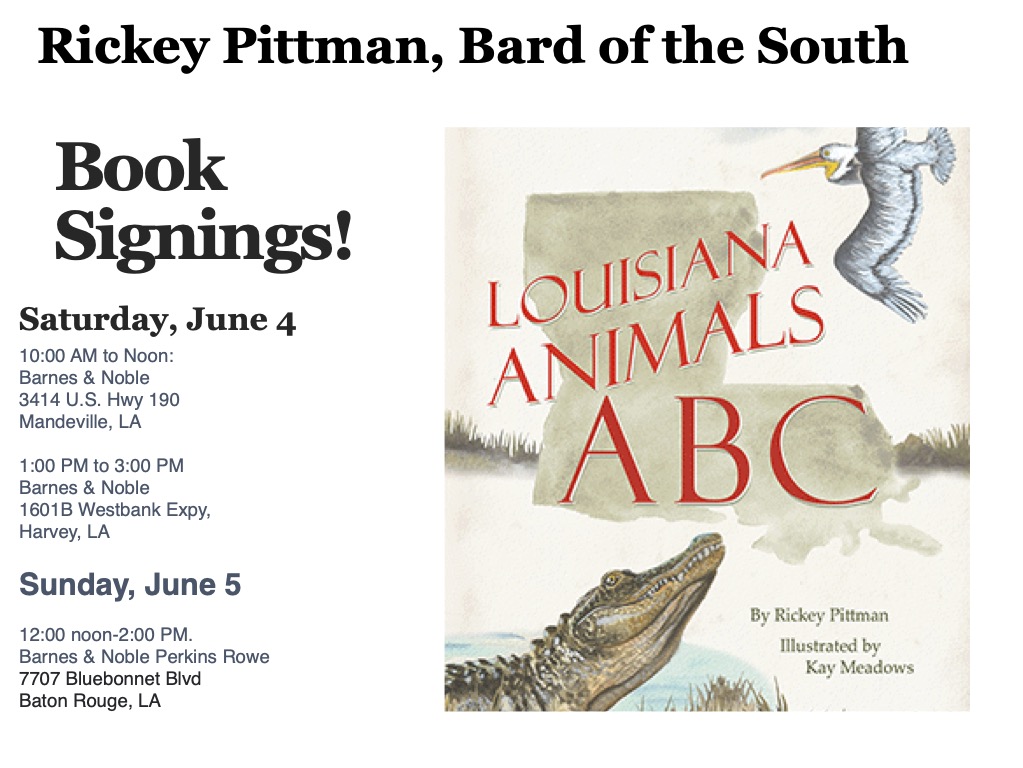

Feel free to share this information! If you are near one of these Barnes & Nobles, stop by for a visit! I’d love to meet you in person!

Feel free to share this information! If you are near one of these Barnes & Nobles, stop by for a visit! I’d love to meet you in person!

Clean Nets

Ever since Indian Territory days, my family has fished this Red River. Mama always said there ain’t no call for us to be ashamed of it neither. She says the first apostles were fishermen, and that if fishermen are good enough for Jesus, then the rest of the world will just have to accept us too.

When they finished the Lake Texoma Dam in 1944, the Red River changed, and our family had to change with it. Now, most of our fishing time is spent on the lake. We also started guiding some, helping those tourists with more money than sense to catch sand bass or stripers, or get them to some ducks and geese in hunting season. They’re surprised we ain’t got no fish sonar or duck radar or fancy gear like that. We just know where the fish are and where the ducks like to go. Ain’t really much to it if a man pays attention.

The life of a fisherman ain’t as simple as it used to be. Now I gotta fool with getting all kinds of permits.

My daddy fishes with us some. He still cain’t read, so I have to read each year’s new rules to him. The state says we gotta count and measure fish, and throw back the game fish if they get tangled up in my nets or traps or get on my trotlines. I have to throw them back even if they’re gonna die. Seems like a waste of good fish. Sometimes I keep them anyway and take them over to Hendrix and give them away to the colored people there. I guess that’s okay, long as I don’t sell them. Sometimes I wonder what these state bureaucrats are thinking. If they’d just talk to a fisherman, they’d get lots of ideas. But I reckon they don’t care for talking to someone who knows how to do something they are passing laws for. No one used to pay us fishermen much mind. Now, we get more attention than I care to have from all kinds of folks, but mostly from rabbit rangers who seem set on catching us breaking some crazy law someone thought up.

Yet, I ain’t got it as bad as some. I read one story of some fellows that got put in the pen for importing half a dozen lobsters that were an inch or so too short. The paper said that government prosecutors worked on this case for six months. Seems like six months of detective work and lawyers would have cost a passel of tax dollars to prosecute

this lobtsergate conspiracy. I hope they don’t get so desperate to keep a job that they would pick on poor fishermen like myself.

We make most of our money off the catfish we sell, but I noticed it’s getting harder to sell them. People are getting attached to that pond-raised catfish, or lately, that catfish or tapia that comes frozen all the way from China. But they don’t taste the same as river fish. Anyone raised on river fish can tell you that.

But what a lot of folks don’t know is that we got all kinds of good fish here, not just catfish. There’s brim, largemouth bass, crappie, gar, drum, buffalo, carp, black bass, sand bass, stripers, hybrids (I reckon a hybrid happens when a sand bass gets to know a striper real well), and spoonbill catfish that we snag down by the dam when the rabbit rangers ain’t around. We eat’em all too.

But even though I spend a good bit of my fishing time on Lake Texhoma, and she works me near to death, I still love that damned old Red River. She’s toned down some since the dam was finished, but she’s still got a mind of her own. She don’t flood much no more, like she did when she devoured the town of Karma, north of Bonham where my grandma had a store. Grandma told me how she and my grandpa just watched the river warsh the whole town away. Weren’t nothin’ they could do bout it. And there ain’t nothin’ lives there now. Lady Red must not have liked that town much.

The river used to have a bunch of logjams, but they’re pretty much all gone now. Daddy said that in his day the logs were so thick you could walk across the river and never get your feet wet. The river’s still got quicksand, even though it ain’t as bad as it was. I don’t know where it went to, but only a few spots are bad to have it now. People who don’t know about quicksand or can’t spot it are in bad shape if they get caught in it alone. It must be horrible for someone to get drownded in mud, being sucked down to the river’s bottom. I only got in quicksand once. Daddy hauled me out and told me how the last person he pulled out of quicksand was a woman, and he had to reach down and pull her out by the hair. She was real dead, he said. And then after making me take a close look at the quicksand, he whipped my little ass with a willow switch real good so I’d remember not to come near it again. I learnt right then what quicksand looked like and I ain’t stepped into it since. A good thrashin’ always helps the memory.

When the water’s high enough, I load up the kids and their grandaddy on the johnboat or airboat, and take them downriver, explaining to them all they need to know ‘bout the river nowadays. When the water’s too low for a boat, I walk its banks on Sundays. Sunday is the only day I don’t fish; it’s the only day our family ever took off from work. I find stuff—old bottles, lots of trash that I guess came down from the dam, ‘cause I sure don’t see no people around to leave it there. Sometimes I think the river’s got a mind of her own and just puts things where she wants when she’s tired of playing with it.

Mama says the river used to be haunted. Gave people some kind of fever that made them start killing folks. Ever time some good ole boy goes on a killin’ rampage, Mama says that the fever’s come back to the Red River Valley. “If’n you ever see someone who don’t belong down there, you be real careful,” she says. “Look at their eyes. The ones with the fever got the same look as a wild dog that ain’t afraid of humans no more.”

“How do people get well from this fever, Mama?” I asked.

“Ain’t but one cure,” she said. “They got to be put down, just like they’s a rabid dog.”

I think that fever’s been around now and then because my family’s found several dead bodies on the river or in the lake through the years. Drownings mostly. Some of them could swim, but they underestimated the strength of the current and the temperamental nature of the river. Sometimes I think she just don’t care for people thrashing around in her and gets riled up and pulls them down. Some of the others I just don’t know how they got there cause they still got their shoes and fancy city clothes on. You can tell they didn’t fall off no boat.

My house ain’t far from the Carpenter’s Bluff Bridge. We see folks down there in summer swimming and diving off the bridge. They go there at night too and build fires and drink and all. I couldn’t sleep one night and I floated down river, sittin’ in the front of the boat just sculling along, and I saw a bunch of folks underneath the bridge. They was sitting in the light of a campfire and I heard them carrying on.

Sounded like they were having a big time. When she’s a mind to, the river knows how to make folks real happy and feel like they belong there. Only difference between these visiting folks and me is that I belong on the river all the time.

My wife Sophie and I had us a bunch of kids, and all of them know how to fish. The littlest ones we teach to get bait. They seine crawfish out of ponds and ditches, dig worms, seine minners out of the creek and sell them so they can have some spending money. But I only got one out of the bunch that’s taken to fishing enough that I know he’ll be a fisherman all his life. When he ain’t in school, he’s with me. Elvin’s a tough one—you can tell by his callused little hands. He doesn’t cry when he gets wet or cold. He don’t mind getting his face blistered by the wind or sun. He works right beside me until the fish are all cleaned and we get everything ready for the next day.

One day we was warshin’ and mending our nets and he says, “You must have the cleanest nets in the river, Daddy. Why you warsh them so much?”

“Dirty nets don’t catch no fish, boy.” Then I tell him what my daddy always told me. “When Jesus called them first apostles, they was warshing nets when he found them. So right away he called them to follow him, ‘cause he knew they were good fishermen. They kept fishing too, only from then on they fished for men. A man’s got to keep his nets clean in life, boy, if’n he wants anything in them but trash.”

We was on the river one afternoon and my boy was walking the sandbars and stepped into some quicksand. I hauled him out of it and whipped his little butt with a willow switch, just like my daddy done me. And I explained to him how the river, she don’t cotton to a man bein’ careless. He’s got to pay attention all the time. I told him how the river’s different now, and how she’ll be different when he’s growed up too. Maybe then she won’t have no quicksand at all, but she does now, and he cain’t go messin’ around in it.

I don’t know why my family likes fishing so. I guess we were just meant to do it. But I know when I feel that tug on my line, and I feel that life there, it feels real good. And when I can sell a pickup load of iced-down catfish to the grocers, and go back home with money, it

makes me feel good to buy my family things they need. Good fishing goes in spells, so I don’t always catch as much as I want. Sometimes the river pushes the fish away from us just to see if we love her enough to stick with her. She ain’t run us off yet. Hell, we ain’t goin’ nowhere.

This is a song I just wrote about my mother—a true story. It is a first draft, so pardon cadence and meter and other issues. I’m probably going to add a chorus to it.

“Two Girls in the Persimmon Tree”

Mitty Beth & Jessie Fae,

Were swinging from grapevines,

Pretending to be Tarzan & Jane,

Having a real good time.

Let’s go fishing, said Jessie Fae,

And a smile came on her face,

I heard the fishing’s good,

In the pool on the Parker place.

Jessie Fae & Mitty Beth,

Went fishing that fine day,

The crossed the fence at the Parker place,

Mitty Beth and Jessie Fae.

They walked into Parker’s pasture,

With bait and fishing poles,

Two country girls out for some summer fun,

To their favorite fishing hole.

The Parker cows had a bull,

They called him Billy the Kid,

Many had tried to ride him,

They tried, but never did.

Sometimes he serviced Parker cows,

When not in rodeos,

But both brought out the mean in him,

Why, I do not know.

Jessie Fae and Mitty Beth,

Saw the bull coming their way

He pawed the ground & lowered his head,

Making the girls afraid.

They climbed up in a persimmon tree,

To escape the angry bull,

They picked the tree’s sweet fruit,

And ate till they were full,

Have you ever eaten persimmons,

After first frost has come?

All the bitterness is gone,

There’s just sweetness on your tongue.

The girls sat until the sun went down,

But the bull, he wouldn’t leave,

He lay down to wait it out,

Till they left the tree.

Their mamas began to worry,

As the sun was setting low,

So they sent the Beechum boy,

As fast as he could go.

Beechum ran the bull away,

And the girls climbed down the tree,

‘They asked for a ride on his horse,

He said, “You’re kidding me!”

Go back home the way you came,

I’ve got better things to do.

Your mamas might tan your hides,

So I’d hurry if I were you!”

This is an essay I entered in a contest as a tribute to my father, Amos (Gene) Pittman

WHAT SATELLITE RADIO TAUGHT ME ABOUT MY FATHER

Country music is me; it’s what I’ve grown up with, and it’s what I do—Scotty McCreery

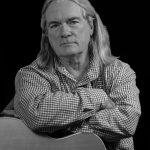

Two years ago, I was driving to South Texas for some gigs and as usual had Sirius Satellite Radio tuned to Willie’s Roadhouse on Sirius Satellite. I’ve always enjoyed the station, but today something felt different. Every song for over an hour, one after the other, was a song I had heard my daddy do. Those songs caused me to remember and realize some things about my father and the music that filled his life, and because I was his son, filled mine.

Amos Pittman was a Haskell County Texas dry-land farmer’s son. He and his two brothers and sister had been raised hard, working the fields of his father’s dry-land farm.

By the time he graduated from high school, two important things happened: First, he learned to play guitar. He was left-handed, but he learned to play guitar right-handed. Second, he was drafted into the Army in the last days of World War II. He was proud of being a veteran his whole life. When he was discharged, while visiting an Army friend, he met my mother, Jessie Fae, and they fell in love immediately and soon married. He was twenty and Jessie Fae was only fourteen. They tried their hand at farming, but the brutal weather of West Texas, financial struggles, the never-ending work, and family conflicts caused them to pack up their few belongings in their 1933 Ford and seek their fortune in Dallas.

Amos found work right away in Dallas as a city bus driver, then with fleet service for American Airlines, which he worked for until he retired. I was born when my mother was seventeen and I grew up immersed in country music. Wherever he went, Daddy always had the car radio on, and to this day I can still hear the voice of Bill Mack in my head. In our Dallas home, Saturday evening was a consistent ritual of country music shows—Porter Wagoner, Wilburn Brothers, Panther Hall, Ernest Tubb and their guests—music that lasted until the evening ended with our watching “wrasslin.”

My father took me to country music concerts in Dallas when we could afford to go. I still recall seeing Charlie Pride and other country greats at Panther Hall and the Sportatorium. I also remember him describing the heart-wrenching songs of George Jones, whom he saw once at a small dive in Dallas. He said Jones’ music touched him deeply, even though Jones was so drunk that night Jones had to lie down on the stage to sing.

Daddy played every venue he could, mostly charity events, and taught me to play guitar. He bought my brother a set of drums and we became his little band. My first guitar was a Silvertone electric ordered from a Sears catalog. The strings were set high, but I played hard every day till my fingertips bled and the callouses and muscle memory of a guitar player were formed. Daddy taught me to play by ear and in any key, and soon I had the same gift he had of being able to hear a country song and play it immediately. I played that catalog guitar with its Black Diamond strings every day, while Daddy picked his Fender Broadcaster. As I learned to play fairly well, I’ve often thought he developed a country music version of the Suzuki method of music instruction.

Today as I sing along with the satellite radio songs, I realize how my Daddy must have had an amazing memory for song lyrics. I can’t explain why I can sing along with a song I hadn’t heard in twenty or more years, other than the fact I must have been so immersed in music as a child. Until his last years, I never saw Daddy sing from a notebook, though I know he must have at times. He knew virtually every song of Hank Williams, Jim Reeves and the other early country singers word-perfect. I started making a list of songs Daddy knew by memory and I stopped counting at 300. As a teen I moved into rock music, but as an adult I moved back to my roots in country music and was surprised to find that I too still had so many of those old songs memorized. Those old country songs hardwired in my memory make up most of the shows I do today.

When the new “pop” sounding country music came along, Daddy stuck with the classics, only occasionally adding a new ballad to his list. He encouraged me to write songs and said he hoped that someday I would make a record.

Daddy died in 2011. I inherited his guitars. The last song I heard him do was “Seven Spanish Angels,” at an Opry in Hendrix, Oklahoma, a year before the strokes and dementia robbed him of the gift of song and speech. I’ve made six CDs now, but my daddy never got to hear any of them.

Now, when I’m performing, dressed in cowboy hat and boots just like he usually wore, I always mention my father somewhere in the show. I wish we could once again sing and play together on stage. I wish I had paid more attention to him, learned more from him. Whenever I visited my mother and I’d strum on his guitar, she would often say, “Your daddy loved that song.”

Yes, it was Willie’s Roadhouse on Sirius XM that helped me reflect on my Daddy and the music he knew and loved. Those were the songs that saturated my boyhood and that touched my memories and formed my heart and soul. Music that I still love. Music that will always be with me and that the crowds I play to will also always hear.

Daddy lived in the age when AM radio, Saturday night country music TV shows and the 45 RPM records he could afford to buy were his teachers. I wish he could have experienced Satellite Radio and Willie’s Roadhouse. Every time I listen to that old music, in my mind, I can hear the twang of that Fender Broadcaster and my father singing those songs. The country music of satellite radio keeps the memory of my father alive in my heart.

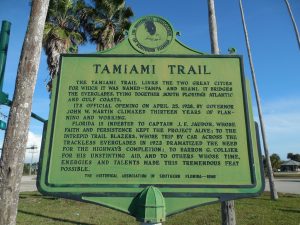

Romance on the Tamiami Trail: A short story by Rickey Pittman

I had seen dynamite used in the movies and read about it in books, but the first time I actually saw dynamite in use was in Naples, Florida. I pulled my car over to watch the road construction men on Highway 30 as they followed a traveling dynamite drilling machine. They would drop the lit stick of dynamite into a hole, drag the blasting map over the hole. The explosion wasn’t very loud, but it was effective in breaking up the limestone rock so the limestone can be used for a base for the road. I found this fascinating. I knew that over two million sticks of dynamite had been used building the Tamiami Trail. Three million had been used in Collier County to create the canals next to the highways. Much of the finances required for this infrastructure came about as a result of the ambition, determination, and resources of Barron Collier, a man blessed with a plethora of resources.

I had seen dynamite used in the movies and read about it in books, but the first time I actually saw dynamite in use was in Naples, Florida. I pulled my car over to watch the road construction men on Highway 30 as they followed a traveling dynamite drilling machine. They would drop the lit stick of dynamite into a hole, drag the blasting map over the hole. The explosion wasn’t very loud, but it was effective in breaking up the limestone rock so the limestone can be used for a base for the road. I found this fascinating. I knew that over two million sticks of dynamite had been used building the Tamiami Trail. Three million had been used in Collier County to create the canals next to the highways. Much of the finances required for this infrastructure came about as a result of the ambition, determination, and resources of Barron Collier, a man blessed with a plethora of resources.

I’ve always enjoyed South Florida—I would live there again if I could. I had only returned to see if I could convince my ex-girlfriend Tessa, to give our relationship another go. I loved this girl fiercely, with her porcelain skin and long black hair that in the sunlight shone like a halo. I had left South Florida and moved to Orlando, an area where a working musician can still make a living. I stopped at the Decadent Dessert Bar on Highway 30A, where Tessa was to meet me. I had performed here many times in the past.

The manager remembered me and asked if I could play for her lunch crowd. I said, “Sure,” and I sat down with a cup of coffee and began to softly plunk on my guitar, searching for the right melody to fit my mood. I finally settle on a song about a man who compared his girl to an Everglades orchid. I sat at a table where I could see into the parking lot, and I saw her step out of her Corvette. Tall, slim and graceful, I felt something in my gut, and choked a bit on the words of the song I was singing. She was dressed in flip-flops, denim shorts, and a flowery blouse. I had loved Tessa, and at this moment I realized I still loved her. I felt like I was a moth attracted to a candle (her), in danger of getting too close to what could destroy me. As she entered the cafe, I ended the song a verse early, set my Taylor guitar on its stand, and stood up. Tessa saw me and smiled, then hugged me. We both sat down at my table.

“Sean, you came back.”

I thought this was stating the obvious. When we broke up, in anger I said I’d never come back to Collier County. Yet, here I was. “Yes, I’m back. Thank you for coming to meet me.” I ordered our coffees—a frozen mocha frappé for her, a double espresso for myself.

“How is your work in Orlando?”

“It’s good. Gigs nearly every night. Pay is good. Better than here.”

“Why did you come back, Sean?”

“I wanted to see you. That’s all.”

“Why?”

I didn’t answer right away. I suddenly felt that nothing I could say would come out right. She looked at me and raised one eyebrow, indicating she expected an answer. “Tessa, I’m not really sure what happened between us. After I left, I realized how much I missed you, needed you. I was hoping we could try again.”

Then she said something that any man who wants the love of his life back doesn’t want to hear.

“I’m seeing someone else now, Sean. He’s a good man and I care for him greatly. He’s an architect. And yes, we are living together.”

“So what happened between us, Tessa?”

“You blew up what we had. You were never around me. You stayed out late with your music gigs, slept late, you drank too much, and when I did go with you for your music, it was horrible. Do you know what it feels like to drive an hour or more to where you’re playing, watch you set up your sound system, sit alone and listen to you for three hours, then watch you pack your stuff, and then have to face a long drive home. Not exactly what you’d call a fun girl’s night out.”

She had a point.

She continued. “Besides, I don’t think it would work if we did get back together. I could give up my present boyfriend, but you’re not going to give up your music. I do believe you love me, and I still care for you deeply, but the road between us has been torn up. We’ve hurt each other too badly to travel down that messy path again. You would just blow it all up again. And now, I need to go, Sean.”

I asked a server to take our picture with my cell phone. We stood with our arms around each other. It was a feeling I remembered. I figured the photo would give me something to ponder—or cry over.

I watched her leave and drive away, just as I heard the road crew set off another stick of dynamite.

Orphanage Road by Rickey Pittman

Highway 77 runs from Corpus Christi to Brownsville, Texas. The road is surrounded by a rich history and legends, and many ghosts. As one enters Willacy County, he or she will pass Orphanage Road. As I knew of no orphanage in operation in the area, I decided to investigate and see how the road obtained its name.

My research revealed that shortly after World War I, Willacy County had assigned fifty black orphans of the Rio Grande Valley to the care of a couple running an orphanage. My research revealed that the orphans must have had a sad life. Ever since the years after the War Between the States, the black families in the Rio Grande Valley were ostracized socially. They lived in isolation, sometimes in fear, but always striving to live unnoticed by the whites and Hispanics who ran the Valley. World War I took many of the black fathers of the Valley. Spanish Flu killed the remaining mothers and the surviving children were collected by Willacy County and sent to the Black Orphanage. Though the children were cared for, the routine of life was difficult for the orphans. Their life there was a one room schoolhouse approach to learning, endless chores, and strict discipline.

Then there was the terrible fire that killed forty-nine of the orphans.

I finally found a survivor of that fire–Hattie. She agreed to meet me at the site of the orphanage. Under a black ebony tree, I studied the ruins of the burned-down dormitory that had once been a home for her and for forty-nine others. Beyond that was a cornfield and one large live oak in the center of the field. Hattie’s caretaker drove her from Raymondville to meet me. Hattie was old now, nearly eighty years old but with the help of her crutch was still mobile.

After we made proper introductions, Hattie said, “So, you want to know about our orphanage. I’ll tell you more than you want to know. Maybe more than you should know.”

What follows is the story she told me.

* * *

“After the fire, I first thought Celia survived. We were best friends. From time to time we would sneak out from their dormitory at night to walk and play in the woods or the cornfield behind the orphanage. Celia always seemed nervous in the cornfield. ‘There’s a Devil’s Tree there,’ she said. ‘With a door. If you ever go near that tree, don’t open that door.’

“‘Trees ain’t got doors, I told her.

‘Some trees do have doors. And once you go in, it’s mighty hard to get out. The Devil’s Tree won’t let you go.’

“One night Celia told me at supper we wouldn’t be able to sneak out because she was going to run away from the orphanage.

“ ’Is that why you is dressed up, Celia’? I said. Celia was all gussied up in a blue calico dress with a red bow in her hair. Nows that I think about it, that was the last time I remember seeing her.

“I thought Celia was kidding about running off and dozed off that night, but later I awoke when she heard something. It sounded just like a window opening. There was just enough moonlight for me to see the open window behind Celia’s bed and the bed was empty too. I went to that window and called out, ‘Celia? Celia, where are you?’

“I slipped out the window and into the cornfield behind the orphanage. I could hear the rustling cornstalks as Celia moving through the field ahead me. The cornstalks behind her snapped in the cold evening breeze. I ran faster to try to catch up. I found myself in front of that oak tree you can still see from the road. The wind was blowing real hard and swirling around my bare feet. Then, I lost her bearings and didn’t know where I was. I wanted to find Celia, but when I heard hourly bell of the orphanage I thought about returning. I eased on up to that gray-barked oak tree with endless arms and fingers. It’s Celia’s Devil Tree, I thought.

“I could see Celia’s name carved on the tree. I touched it and the bark felt warm. And, as I stared at it, the tree seemed to open and I passed out.

“I woke near dawn, and for a moment I still couldn’t remember where I was. Crazy houghts rushed into my mind, one after the other. Then it came back to me: Celia had run away and I had followed her into the cornfield and to the Devil’s Tree. I decided I better get myself back to the orphanage.

“When I stood up, I saw black smoke rising from the direction of the orphanage. I ran as fast as I could back to the orphanage, only to find it all burned up.. Mr. and Mrs. Smith, the orphanage director and his wife, were talking to the Sheriff and so I ran up to them. The director’s wife said, “There’s Hattie! At least one made it out alive! Hattie, oh Hattie . . .”

“I asked them what happened.”

‘A fire, Hattie,’ the director said. ‘All the other orphans were lost.’

“No, not all,” I said. “I followed Celia out the open window. She was running away and I wanted to bring her back. ”

“The director shook his head and he said. ‘Hattie, we found Celia. She died with the others.’

I set down my pen. “I’m so sorry, Hattie.”

Hattie said, “They dug her a grave with the other orphans, but I don’t think she’s gone. Deep down I think she’s still with us and always will be in some way.”

“I hope so, Hattie.”

In the weeks following, I interviewed as many as I could, but no one knew how the fire started, only that forty-nine orphans died. There’s not much written about the orphanage either—no court records, no diaries, no letters. One night I was driving into Harlingen and passed Orphanage Road. I went to the next exit and turned around. Something bothered me and I felt no peace. I turned onto Orphanage Road from 77 and as I drew near to the site of the orphanage, I passed a little black girl on the side of the road, waving to me. She wore a blue calico dress and had a red bow in her hair. I hit the brakes and turned the car around, but found no little black girl. Only a thick mist that faded out into the cornfield. I pointed my car’s headlights into the cornfield and could just barely see the twisted, gnarled limbs of an oak in the distance.

I’ve driven down Orphanage Road several nights since then. And every time, I’ve passed the same little girl on the side of the road, but she’s never there when I turn around.

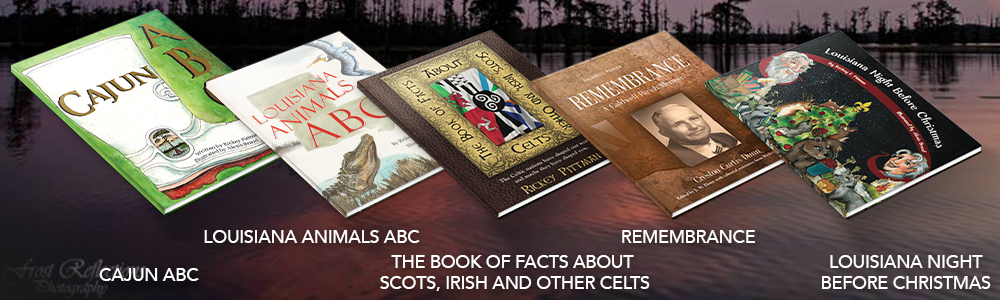

Rickey Pittman, Bard of the South

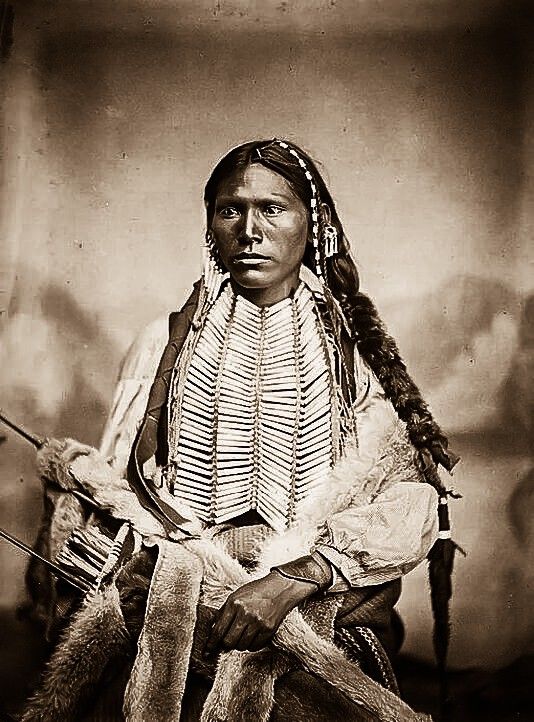

Pine Knot’s Last Prayer

Pine Knot cursed and popped the back of the lead mules again with his whip. “Damnation, what is wrong with you mules today? You poke along like I’m taking you to a funeral. I got to get these pumpkins up to Jacksoboro and I don’t have time to fool with you. Ought to sell every durn one of you and buy some oxen. What do you think, Hank?”

“Uh huh,” Hank said. He lifted the water jug to his lips and drank deeply.

“Go slow on the water, Hank. I’d like to have some. Hank, you should spit out your tobacco before you take a drink. Swallowing that tobacco juice will make you sick.”

“Uh huh.” Hank set the empty jug down.

“Never you mind, Hank. At Howard Creek Road we’ll refill it at the spring. That is, if these durn mules will cooperate. Go on, mules!”

At the spring, Pine Knot stopped the wagon and studied a line of Indians in the distance. “Ah, hell, Hank. We best get out of here.” The road was too narrow and the terrain too rock covered to turn the team around where he sat, but he saw a wider area ahead where he ought to have enough room to circle back the other direction, so he eased the team on, hoping that if he didn’t pay them no mind, the raiders wouldn’t be interested in their scalps or the mules.

Hank stood, leaned forward slightly and peered at the Indians. He drew his imaginary pistol, pointed it at the Indians, and started firing.

“You sit yourself down, you idgit, afore you get them riled up. Put up your pistol, Hank. They might not can tell you don’t have a real one.”

Hank sat down, but the Indians started slowly moving their way, and Pine Knot guessed that since their hair was cut short on the right side of their shoulders they were Kiowa. He muttered, “God in heaven, I wish I was Elijah and could call fire down from heaven on these heathen.” The wagon had nearly turned completely around.

Hank stood up and turned to face the Kiowa. One hand held the reigns of a horse long ago shot out from under him and in the other, his imaginary pistol blazed away like he remembered it doing at Chickamauga.

Pine Knot cursed his luck. His shotgun lay right next to him, but he knew that its two shots would be all he could fire if they attacked. He wouldn’t have time to reload the muzzleloader and the Indians would cut them to pieces. “Durn it to hell,” he said. “How’d I get stuck here with one shotgun and an idiot with an imaginary pistol? God, don’t let us die! Make them go away. I want to keep my hair!”

War whoops and the pounding hooves of horses revealed the answer to his prayer.

A boy and a man both climb Mount Baldy

“The Child is father of the Man”—Wordsworth

My favorite day in nature happened twice on the same mountain. As a Boy Scout, I was the only boy in our troop in Dallas to be sent to Philmont Scout Ranch. My early years of reading had fueled my passion for history and the wilderness, and though I had gained some camping experience in scouts already, this was the camping trip that would give me my finest and favorite day in nature.

The Philmont experience took our Dallas busload of young campers on a two-week trek through the Philmont Scout Ranch. We hiked a total seventy-two miles through various terrains. Passing other hiking groups struggling with their uncooperative burros, we were glad we chose to carry our gear in. I tried to observe everything I could—tracks of animals, trail signs, the types of trees and while many boys kept their tired eyes on their tired feet, I kept looking ahead for the various birds and wildlife I knew lived on the Philmont Ranch.

The high point of our trip (pardon the pun) was climbing Mount Baldy, the third highest mountain in New Mexico. It was not an easy climb, even for athletically inclined teenage boys. We followed the switchbacks, stopping every so often to catch our breath. We finally snaked our way to the rocky bald top.

At the top, the misty, cold, and stiff wind greeted us. The panoramic view was amazing. Our guide pointed out the five states we were looking down on. Bighorn sheep approached us and ate trail mix from our hand. On the summit, I picked a few small delicate flowers, intending to dry them and keep all my life as a reminder of this mountain experience.

Laurel Bleadon-Maffei said, “I found my heart upon a mountain I did not know I could climb, and I wonder how many other pieces of myself are secreted away in places I judge I cannot go.” I think I found and touched, or the mountain I climbed found and touched, secret places in me that I didn’t know were there.

I said in my introduction that my favorite day happened twice on the same mountain. When I was forty, I climbed Mount Baldy again. In 1990, I decided it was time to reinvent myself. I floundered with selling jobs for a while, but I got a real break when I was offered a scholarship at Abilene Christian University. I knew it was time to reinvent myself. One of the classes I elected to take was backpacking. The final part of this course was a week’s camping trip in the mountains of New Mexico, close to, but not on the Philmont Scout Ranch. We walked fifty-two miles in our trek.

One day of that trip was devoted to climbing Mount Baldy. Once again, I followed the switchbacks up that mountain, stopping every so often to catch my breath in the thinning mountain air. The stiff, misty cold wind increased as we climbed. At the summit, our class shared a canned Dr. Pepper and took our group photos. Once again, I looked at the five states about me. Once again, I fed gorp (trail mix) to the Bighorn sheep that greeted us near the summit. I don’t know the life expectancy of such sheep, but perhaps they were the same herd, or perhaps descendants of the ones I had seen as a teen. Once again, I picked the same type of small delicate mountain flower. The one I had picked as a teen had vanished somehow somewhere in my wild teenage years, and I vowed that I would not lose this one.

Now, many years after that last climb of Mount Baldy, in the window of my mind I can still see that mountain, the teenage boy who struggled to its summit and the forty-year-old man on a search to reinvent himself yet once again. Both the first and second flowers I picked on that mountain are lost to me, but that day, that day in two parts, will never be lost.

THE MAD MOUNTIE OF MYSTERY MOUNTAIN

Beth’s two children were laughing as they tried to catch the red leaves raining down upon them. A cold wind brought the promise of frost by morning and she shivered as she herded the children to stay on the narrow path. A fall in the river would be dangerous this time of year. She cursed herself for taking this assignment from her publisher. Some vacation. Her assignment? She was to write a story about the legendary Mad Mountie of Mystery Mountain. Preferably, he wanted her to find and photograph the man as well as collect anecdotes. So far, she had found a few who had seen him, or whose parents had seen him, but few details. The legend claimed that he had been sent years ago to Mystery Mountain to find an escaped criminal who now lived wild in the woods of British Columbia with the Spirit Bears, rare white-coated black bears. The Mountie, who had twenty years of experience with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, had not found the criminal and in fact, had never returned to duty, though he had been seen many times. It was thought that the assignment and the vast solitude of the Canadian forests had made him crazy.

The woods can do that sometimes.

As Beth walked on, she glanced up, and she instinctively reached for the children’s hands. A man in a faded Red Serge, the dress tunic of the Mounties that had once dripped with its scarlet red color, was approaching. As he drew near, he showed a toothless grin, tipped his worn, felt campaign hat politely, and said, “I haven’t met anyone on this path in several years. I am Owen McKenzie, with the Royal Canadian Police, at your service.”

“I am pleased to meet you, Owen.” Beth contemplated the faded blue breeches and could just barely see the yellow stripe indicating the cavalry history of the Mounties. Physically, she could tell that the years had not been good to him. She wondered if serendipity had worked its magic and she had been led by fate to find the legendary, Mad Mountie. “I am Beth Cameron, and these are my children. I’m a reporter and I’m on a working vacation. I would love to talk to you about your work with the RCP. I would so appreciate this favor.”

Owen said, “It’s been such a long time since I’ve talked to anyone. The day is getting late. I assume you walked up from the cabins at the Mystery Mountain Park and we should return there now while there is light. I’ll be happy to answer any questions, though I may have a favor of my own to ask of you.”

“I will be glad to honor any favor you may ask,” Beth said. As they returned on the path they had started on, Beth decided to start gathering information. “You know people say you are mad.”

He nodded. “Yes, sometimes I think the same thing.”

“Where do you live?” Beth asked.

“In a tent in the woods. For many years I’ve traveled throughout British Columbia searching for the escaped brother of Gilbert Paul Jordan. But he has proved to be elusive. Have you heard of him?”

Beth replied, “I’ve heard of Jordan, but not his brother. Didn’t they call him the Boozing Barber? He liked to prey on Native American women in Vancouver’s skid row.”

Owen said, “His brother had the same evil in him. I was sent to find him and bring him in, and I vowed to never return to duty until I do. You know what they say about us Mounties?”

“You always get your man?”

“Yes, we always get our man, though as it’s been said, not always quietly. And I’ve got him cornered this time. He will certainly be going back to prison very soon.”

At the cabin, Owen helped her start a roaring fire. Beth made a pot of tea and warmed up a soup she had made the day before. After they had eaten, she put the kids to bed on their cots. They begged Owen to tell them a story of his adventures. He told them of his first sighting of the Spirit Bear and how the Native Americans had deliberately not shared with the white settlers the knowledge of these creatures who lived deep in the dark and quiet recesses of the Canadian forest. Jordan’s brother had found them too and become attached to them. Owen said he could count on Jordan to always return to the parts of the forest where they lived. When the kids had drifted to sleep, Owen said he must excuse himself and return to his tent.

“Will we talk again?” Beth asked.

“No, but I will still count on you to grant me the favor I’m going to ask of you.”

“Anything. What is it?

“You will know in the morning. Goodnight, Beth.”

The cabin’s fire had died to ashes, and when Beth woke in the morning, she revived it. She opened the cabin door and gasped at what she saw. Lying on the porch, bound hand and foot was a bearded man with a note pinned to his jacket. The note read:

Beth: Here is Jordan’s brother. Call the Royal Canadian Police at 911.They will assist you. Tell them that Owen McKenzie always gets his man.