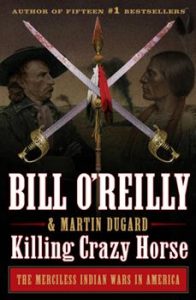

Killing Crazy Horse by Bill O’Reilly & Martin Dugard: A Short Review

by Rickey Pittman, Bard of the South

“How little it takes to bring out the bloodthirsty savage in each one of us.”

― Marty Rubin

“There are many humorous things in the world; among them, the white man’s notion that he is less savage than the other savages.”

― Mark Twain

Every since I was a boy, I have had a fascination with Native Americans. By the time I was fifteen, I had read every book about American Indians in the Bachman Lake Branch of the Dallas Public Library. Fueled by reading these books and by the westerns on television, I memorized every fact I could, and their stories fueled my play, imagination, and fantasies. I have an impressive collection of books related to Native American history and culture–including biographies, historical events, and languages including the Comanche, Creek, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw. So, I was delighted to read Killing Crazy Horse by Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard. Having read several of O’Reilly’s books, I was not surprised to find this a good read, with many facts and thoughts that would prove useful to my historical Songs & Stories school programs, my reenacting events, my western novel and stories projects (hopefully, soon to be published), and in my college class of American literature.

The book is well-written, taking the reader through a fast-paced journey through America’s history with the Native Americans our founders met and encountered. From the Creek Fort Mim’s Massacre (1813) to the surrender of Chief Joseph of the Nez Percé (1877), O’Reilly weaves an honest and often disturbing tapestry of Native American history. The character, world views, families, and lives of key players in this distinctly American drama–both American and Indian–are described, quoted and illustrated with details that are revealing and sometimes shocking. The reader learns that the Hollywood versions of America’s history and people are often glamorized and incorrect. The book has valuable footnotes, an excellent index, and a comprehensive bibliography.

I did discover one small historical error. On p. 111, the author has 1860 Texas Rangers armed with .45 -caliber “Peacemaker” pistols, instead of the 1851 Colt Revolver. (The .45 Peacemaker was not in use until 1872.)

This is not a book containing the usual stereotypes. Many Native Americans in these wars often proved themselves to possess almost unbelievable cruelty. The torture scenes and violence they inflicted on other Native American tribes, Mexicans, and Americans, are horrifying. And the treatment Native Americans received from the hands of other Native Americans, Mexicans, Americans and the U.S. Government is just as shocking.

If you have an interest in a good overview of Native Americans and their wars, this is a book that will prove to be a valuable read.

An epigraph is a short quotation, phrase, or poem that is used at the beginning of a piece of writing that suggest a theme or suggest a mood or used to steer the reader’s mind in some direction. I like to use epigraphs in my writing, sometimes before every chapter in a book or novel or at the beginning of short stories or poems, directly under the title. Here is a list of epigraphs I used in my novel, Under the Witch’s Mark: (Ordering information is below)

An epigraph is a short quotation, phrase, or poem that is used at the beginning of a piece of writing that suggest a theme or suggest a mood or used to steer the reader’s mind in some direction. I like to use epigraphs in my writing, sometimes before every chapter in a book or novel or at the beginning of short stories or poems, directly under the title. Here is a list of epigraphs I used in my novel, Under the Witch’s Mark: (Ordering information is below)

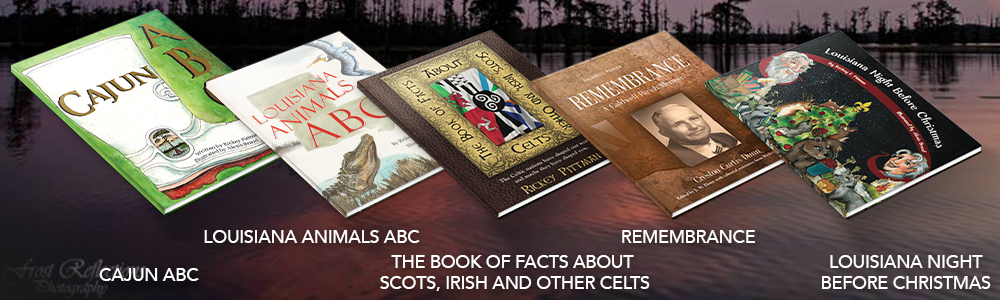

These are just a few of the stories I could share, but if you would like to read more, I would recommend the following books:

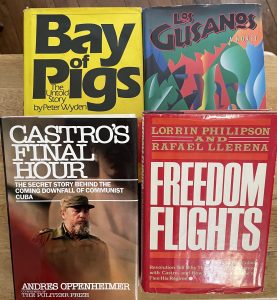

These are just a few of the stories I could share, but if you would like to read more, I would recommend the following books: I lived in South Florida (Naples) for a couple of years and there I encountered and learned much about Cuba and the thousands who had managed to flee Cuba. Last night, I watched a Netflix movie, WASP NETWORK, and this brilliant film revived many memories and feelings I had experienced as I worked among and with the Cuban community. The 2019 film is based on a book, The Lost Soldiers of the Cold War: The Story of the Cuban Five, (a book I just ordered). Oliver Assayas wrote and directed the movie. Much of the dialogue is in subtitled Spanish. The actors’ performance (including Penelope Cruz) is amazing. The plot is based on the lives and experiences of Cuban spies operating in South Florida in the 1990s. There are no happy endings for the Cuban Five.

I lived in South Florida (Naples) for a couple of years and there I encountered and learned much about Cuba and the thousands who had managed to flee Cuba. Last night, I watched a Netflix movie, WASP NETWORK, and this brilliant film revived many memories and feelings I had experienced as I worked among and with the Cuban community. The 2019 film is based on a book, The Lost Soldiers of the Cold War: The Story of the Cuban Five, (a book I just ordered). Oliver Assayas wrote and directed the movie. Much of the dialogue is in subtitled Spanish. The actors’ performance (including Penelope Cruz) is amazing. The plot is based on the lives and experiences of Cuban spies operating in South Florida in the 1990s. There are no happy endings for the Cuban Five.