Orphanage Road by Rickey Pittman

Highway 77 runs from Corpus Christi to Brownsville, Texas. The road is surrounded by a rich history and legends, and many ghosts. As one enters Willacy County, he or she will pass Orphanage Road. As I knew of no orphanage in operation in the area, I decided to investigate and see how the road obtained its name.

My research revealed that shortly after World War I, Willacy County had assigned fifty black orphans of the Rio Grande Valley to the care of a couple running an orphanage. My research revealed that the orphans must have had a sad life. Ever since the years after the War Between the States, the black families in the Rio Grande Valley were ostracized socially. They lived in isolation, sometimes in fear, but always striving to live unnoticed by the whites and Hispanics who ran the Valley. World War I took many of the black fathers of the Valley. Spanish Flu killed the remaining mothers and the surviving children were collected by Willacy County and sent to the Black Orphanage. Though the children were cared for, the routine of life was difficult for the orphans. Their life there was a one room schoolhouse approach to learning, endless chores, and strict discipline.

Then there was the terrible fire that killed forty-nine of the orphans.

I finally found a survivor of that fire–Hattie. She agreed to meet me at the site of the orphanage. Under a black ebony tree, I studied the ruins of the burned-down dormitory that had once been a home for her and for forty-nine others. Beyond that was a cornfield and one large live oak in the center of the field. Hattie’s caretaker drove her from Raymondville to meet me. Hattie was old now, nearly eighty years old but with the help of her crutch was still mobile.

After we made proper introductions, Hattie said, “So, you want to know about our orphanage. I’ll tell you more than you want to know. Maybe more than you should know.”

What follows is the story she told me.

* * *

“After the fire, I first thought Celia survived. We were best friends. From time to time we would sneak out from their dormitory at night to walk and play in the woods or the cornfield behind the orphanage. Celia always seemed nervous in the cornfield. ‘There’s a Devil’s Tree there,’ she said. ‘With a door. If you ever go near that tree, don’t open that door.’

“‘Trees ain’t got doors, I told her.

‘Some trees do have doors. And once you go in, it’s mighty hard to get out. The Devil’s Tree won’t let you go.’

“One night Celia told me at supper we wouldn’t be able to sneak out because she was going to run away from the orphanage.

“ ’Is that why you is dressed up, Celia’? I said. Celia was all gussied up in a blue calico dress with a red bow in her hair. Nows that I think about it, that was the last time I remember seeing her.

“I thought Celia was kidding about running off and dozed off that night, but later I awoke when she heard something. It sounded just like a window opening. There was just enough moonlight for me to see the open window behind Celia’s bed and the bed was empty too. I went to that window and called out, ‘Celia? Celia, where are you?’

“I slipped out the window and into the cornfield behind the orphanage. I could hear the rustling cornstalks as Celia moving through the field ahead me. The cornstalks behind her snapped in the cold evening breeze. I ran faster to try to catch up. I found myself in front of that oak tree you can still see from the road. The wind was blowing real hard and swirling around my bare feet. Then, I lost her bearings and didn’t know where I was. I wanted to find Celia, but when I heard hourly bell of the orphanage I thought about returning. I eased on up to that gray-barked oak tree with endless arms and fingers. It’s Celia’s Devil Tree, I thought.

“I could see Celia’s name carved on the tree. I touched it and the bark felt warm. And, as I stared at it, the tree seemed to open and I passed out.

“I woke near dawn, and for a moment I still couldn’t remember where I was. Crazy houghts rushed into my mind, one after the other. Then it came back to me: Celia had run away and I had followed her into the cornfield and to the Devil’s Tree. I decided I better get myself back to the orphanage.

“When I stood up, I saw black smoke rising from the direction of the orphanage. I ran as fast as I could back to the orphanage, only to find it all burned up.. Mr. and Mrs. Smith, the orphanage director and his wife, were talking to the Sheriff and so I ran up to them. The director’s wife said, “There’s Hattie! At least one made it out alive! Hattie, oh Hattie . . .”

“I asked them what happened.”

‘A fire, Hattie,’ the director said. ‘All the other orphans were lost.’

“No, not all,” I said. “I followed Celia out the open window. She was running away and I wanted to bring her back. ”

“The director shook his head and he said. ‘Hattie, we found Celia. She died with the others.’

I set down my pen. “I’m so sorry, Hattie.”

Hattie said, “They dug her a grave with the other orphans, but I don’t think she’s gone. Deep down I think she’s still with us and always will be in some way.”

“I hope so, Hattie.”

In the weeks following, I interviewed as many as I could, but no one knew how the fire started, only that forty-nine orphans died. There’s not much written about the orphanage either—no court records, no diaries, no letters. One night I was driving into Harlingen and passed Orphanage Road. I went to the next exit and turned around. Something bothered me and I felt no peace. I turned onto Orphanage Road from 77 and as I drew near to the site of the orphanage, I passed a little black girl on the side of the road, waving to me. She wore a blue calico dress and had a red bow in her hair. I hit the brakes and turned the car around, but found no little black girl. Only a thick mist that faded out into the cornfield. I pointed my car’s headlights into the cornfield and could just barely see the twisted, gnarled limbs of an oak in the distance.

I’ve driven down Orphanage Road several nights since then. And every time, I’ve passed the same little girl on the side of the road, but she’s never there when I turn around.

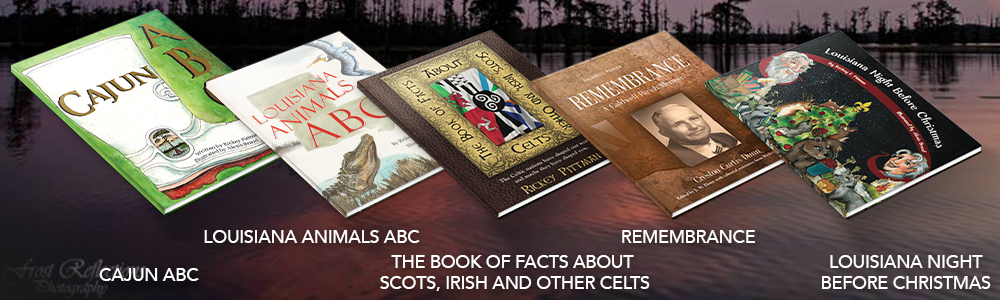

Rickey Pittman, Bard of the South